“Without the Divine” by Olivia Maday & “Twilight Language” by Josiah Bolth

Living Arts of Tulsa

August 19, 2025

“Room will be dark. Proceed with caution,” reads the sign on the main door of Living Arts. Coming inside from a blazing summer afternoon, I found it more of a comfort than anything else to enter what felt like a cave: cool, nearly silent, and so dark that I had to stand still as my eyes adjusted.

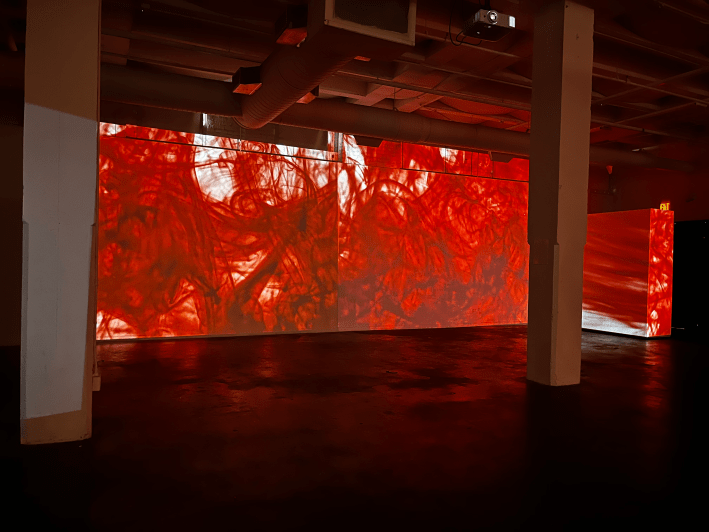

There’s a practical reason for the darkness: Olivia Maday’s exhibit “Without the Divine” (one of two in this current Living Arts show, up through August 23) is a nine-channel video installation, with images projected on nearly every surface of Living Arts’ west gallery walls, and light is the enemy of visibility in art that involves projections.

There’s a metaphorical reason for it, too: this work takes inspiration from the Greek myth of Persephone, who was abducted (and in some versions raped) by Hades and ultimately became queen of his kingdom of death, while also serving as goddess of spring for half of the year. The themes in Persephone’s story resonate with those, like me, who like our deities on the untidy side, capable of embodying several truths at once. As violence against women continues apace and women artists continue to challenge male-dominated representations of their lived realities, those themes have staying power.

For Maday, a Boston-based recent MFA grad from Tufts University, such “chthonic” (i.e., related to the underworld) feminist themes are a throughline in her performance and video art, which links 19th-century elements like veils and cabinet cards with contemporary media and materials like raw meat to challenge patriarchal views of women and reassert female agency. One strain in Persephone studies argues that the goddess' story is one of empowerment and renewal, not victimhood or subjugation; it’s this strain that Maday takes up in “Without the Divine,” which appears to be an iteration on her 2024 work "Chthonic Ode.”

The predominant visual in the show is a suspended red liquid, flowing in slow motion down multiple walls. Two signs in the gallery warn of flashing lights and implied sexual violence, both of which appear in subtle forms: a faint shuddering mirage of red light on a black screen; a nude woman’s body flexing like an octopus behind a pane of glass smeared with pomegranates (the fruit Persephone ate that condemned her to stay in the underworld); red hands, backs, and thighs in videos projected onto Mylar panels and spilling over onto the dark wall behind them. Now and then, lines of poetry appear on two small offset walls, odes to defiant self-creation. A barely audible roar accompanies the videos, adding to the feeling of hovering between worlds created by the repetitive, floating images.

I thought about concealment and revelation when standing in this black/red/silver space, about the grotesque and the erotic, about blood and juice and the messy power of the life force that moves even through death, without regard to the dictates of gods or men. “Without the Divine” is strong work on a strong theme, and I hope Maday continues to go further with it all, maybe adding a greater variety of videos and a sound score that does a little more than ominously hum. As dark as it is in this thoughtfully conceived exhibit, it could shine more light by being darker, and wilder, still.

Walking through black curtains into the second exhibit in this show was like moving into another planetary atmosphere: scorching sun and wind rather than liquid and earth, masculine rather than feminine. But the visions here, in Josiah Bolth’s “Twilight Language,” complement Maday’s work in their phantasmagoric chaos. Bolth is a New Orleans-based oil painter who seeks, as he says, “the creation of a figurative space replete with the artifacts of culture and history, of disorganized and unfocused consciousness, murmuring with the promise of stranger forms waiting to be conceived.” As with most artspeak (Maday’s, too), all of those words say less than the work itself, which mashes up many myths and totems against the backdrop of a terrifying present.

After the murky, pulsing, liminal flow of “Without the Divine,” these paintings made me both shudder and laugh. With decisive brushstrokes, extreme perspectives, and a confident use of unexpected color, Bolth gives us a fleet of white pegasi seen through a bombsight; a flying circle of black dogs looking down on a disemboweled Cessna; a crowd of fluorescent cats in an alley, eyes glowing with nighttime light; a green-masked dog pausing in mid-crotch-lick; an alien dunking a basketball on a court with industrial smokestacks in the background; crows perched on playground equipment, lit by a black, kidney-shaped sun. The water in this world is radioactive, bright orange; the skies are on fire; threats of exposure, entrapment, and attack are everywhere. The cultural and historical artifacts Bolth uses speak to a legacy of death—with that as our heritage, it’s no wonder that what lives best in this space is surreal, both hilarious and psychotic.

Josiah Bolth: "Deathtrap," "Airstrike," "Nightvision," and "The General Zapped An Angel" | photos by Alicia Chesser

The human forms in Bolth’s paintings are almost all faceless: red skeletons filled with beefy black, eye sockets glowing scarlet. They look less hollowed out than about to overflow with dark goo. Some are got up as cowboys; others are accompanied by elements associated with global Indigenous cultures. Maybe the strongest piece in the show, “Big Wheel,” puts a group of those shadow cowboys, guns drawn, on five panicked carousel horses, whose muscles swirl like the whorls in the cowboys’ clothes. Mirrors behind the figures make it hard to be sure who’s aiming at whom—a moment of total raging mania, frozen in bizarre, circusy fun-time. You can almost hear the carousel music going haywire on this ride from hell.

Setting aside the similarly black-red figures (with breasts) in “Hellfire,” this doesn't seem to be a world that welcomes women. Traditionally female spaces—laundry lines, a kitchen window with a pie in it—are populated by ghosts and fairies; a rictus-grinning lady driving a car has light beams shooting out of her eyes; another female figure is called simply “La Fantoma.” This North American psychosphere has excised the feminine pretty much entirely, or at best distorted it into something otherworldly—an argument with which Maday might agree.

Josiah Bolth: "Hellfire," "The Dinner Gong," and "Ghost Laundry" | photos by Alicia Chesser

One of Bolth’s paintings shows a group of orcas swimming in a lake as luridly hued and spangled as a Lisa Frank sticker. Wildflowers bloom in the foreground, as distant gray mountains frame the weirdly orange-red water. The Eye of Sauron looms on the horizon as fiery smoke (or is it just the sunset?) plumes skyward. The title of the work, it pleases me to report, is “Oklahoma.”

Both of these shows go a long way toward helping make some very upsetting contemporary feelings visible. This isn’t art that tells us what to do about the dangerous state of things; it’s art that, to me, says, “You’re not crazy to feel crazy. And in fact, there might be sanity and even power in naming your place, outlandish as it may be, in this hellscape.” What life can be born out of all this darkness? It's a good question, and I'm grateful to Maday and Bolth for raising it.