"Southern Ems" by Regina Dao, Nic Annette Miller, and Đan Lynh Phạm

Positive Space Tulsa

Through April 26

“Our artist statement is here,” Regina Dao said, directing me to the left as I walked into Positive Space’s new exhibit Southern Ems. “And our timeline”—she pointed to the opposite wall—“goes this way.”

For as many individual pieces as there are in Southern Ems, the space between them feels vast. The short journey around this small white room is full of distances, covering miles, centuries, and unquantifiable experiences: from Vietnam to Oklahoma; from family roots to family branches; from 1858, when French colonial rule began in Vietnam, to 2025, when three Tulsa-based Vietnamese American artists—Dao, Nic Annette Miller, and Đan Lynh Phạm—created this group show.

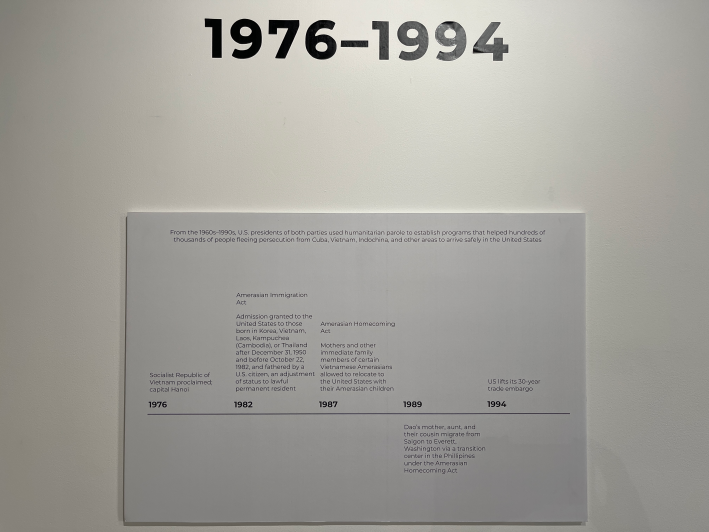

That feeling of distance creates the show’s delicacy. Phạm’s pieces are literally translucent; Dao’s are suspended overhead or balanced on pedestals; Miller’s hover midway up the walls or rest on the floor. A thin line separates global stories from personal ones on three wall panels that mark the historical timeline and move you from one artist’s work into the next. Above: relations between powers, proclamations of war, international relocation programs. Below: the movements of Dao’s mother, aunt, and cousin, of Phạm’s family, of Miller herself.

The lightness in the room feels like a whisper through time. Generational inheritances see-saw across the show and travel forward through conflict, migration, and love. Many of these pieces are neutral-toned, but there are notable exceptions, like the bold red pen Miller used to correct a 1975 newspaper report, or the baby’s-room hues of Phạm’s haunting “Security Blanket,” the grid-like shadow behind which shows up as strongly as the quilted form itself. Miller’s poem about mushrooms (printed on fluorescent yellow paper), her ASL poem “The Land” (which runs on an old-school iPhone), and her video installation “Our Tones, Our Wrists, Our Home” (located somehow outside the timeline as it plays in a corner down a hallway, moving with its own pulse of communication) are likewise vivid in color, the latter topped with a migratory ascent of orange and black butterflies.

art by Nic Annette Miller and Đan Lynh Phạm | photos by Alicia Chesser

Lightness doesn’t mean a lack of weight, and a sense of distance doesn’t mean something’s actually far away. There’s space in here to feel these long, deep journeys. The personal histories on those three timeline panels hang from that line like Dao’s bowls hang from the ceiling—bowls among which I unexpectedly found myself, almost banging my head against them, as if they’d been caught in the act of falling around me, or were waiting for a familiar hand to reach up and take one down the way a grandma would in her well-loved kitchen. I put a hand up to shield the hanging installation from my movement and noticed, below my sight line, a broken plate painted with the words “No one thought to save us, too.”

art by Regina Dao | photos by Alicia Chesser

The detail in these works—the gritty glaze on those bowls, for instance, which feels like captured debris, or the globular geometric shapes of Phạm’s lantern quartet—creates an intimacy within all that space, inviting the senses to switch on. The density of memory, effort, and physical presence is here in full, as in the tilted, hollowed-out sweep of Dao’s “Eternal Warrior” and the vigorous, muscular striations of the sculptural woodcut and serigraph prints in Miller’s “She Takes She Shares,” part of her ongoing “fish market” series.

There’s humor here, too: several of the fish sculptures are literally displayed on ice. The promise of flavor in Miller’s work actually made me salivate. In addition to the names of all those fish, there are the titles of four potent little short stories: “Boiled Lobster,” “The Yellow Thing,” “Spring Roll Buffet,” “Sardine Toast.” Embedded in these tales are the awkward, generous, confusing human stories that link families through food, tracing belonging within the fractures of geography, language, and time.

art by Nic Annette Miller | photos by Alicia Chesser

Heritage becomes a living, shareable thing in Southern Ems: it’s something you place in your hand, bring to your lips, wrap yourself up in, communicate through, carry with you. On the two side-by-side screens in “Our Wrists, Our Tones, Our Home,” Miller and her mother, who is deaf, say a series of words and phrases in five sign languages, including one called Home, which is distinct to their family. Their tender, intergenerational, contrapuntal duet—like Phạm’s “Security Blanket,” in which a comfort object is simultaneously an X-ray scan—brought tears to my eyes.

art by Nic Annette Miller (L) and Đan Lynh Phạm (R) | photos by Alicia Chesser

This isn’t a showy show; it asks you to slow down, to stand in the midst of a long history and listen for the ways it speaks in the present. Southern Ems is timed to the 50th anniversary of the Fall of Saigon; “ems” is the Vietnamese word for “little sisters.” I felt both the loss and the closeness in this exhibit, in which these three sensitive and thoughtful artists, finding themselves here after half a century of migration, have built a room together that somehow feels like home. It’s not an easy story. It’s a true one.