In the middle of a large room in downtown Tulsa, there’s a paint-splattered prison shirt, v-necked, grey. A tag across the pocket reads “Starlite Walker”; below that, in chunky black marker, is written, “I speak in absolutes”. The shirt belongs to William Livingston, and the text is an attempt to represent oneself in a different way. That’s a tough thing to do in prison.

In “A Relentless Pursuit: 217 Prison Concert Posters,” now on display at 101 Archer, the question of how someone presents themselves rises above the art itself. Livingston went to prison in 2010 for vehicular manslaughter and drunk driving after he struck a bicyclist with his car; he spent 12 years across Lawton Correctional Center and Joseph Harp Correctional Center in Lexington, Oklahoma. During his imprisonment, he slowly began to claw his life back, bit by bit, through his art practice.

The 217 concert posters—produced and distributed for free, on a press rigged from basic materials found in the prison—show the breadth of Livingston’s talent: they range from realistic to abstract, loud to quiet, and run the gamut from large national acts like Modest Mouse and Jenny Lewis to local Tulsa ones like Poppa Foster, The Fabulous Minx, and Winston Churchbus. They’re strong posters; even more so when one considers that they were produced inside a penitentiary. Many of them contain stamps reading “Prison Art” or “Don’t Drink and Drive.” But the strongest piece of art in the show is Livingston’s narrative, told through his possessions.

On white pillars scattered throughout the show are Livingston’s objects from his time in prison. Next to his grey, v-necked shirt sits a ratty pair of blue jeans with patches sewn under the holes, which Livingston says he bought used in the prison yard and resewed over and over. “Just trying to have pants,” the caption reads.

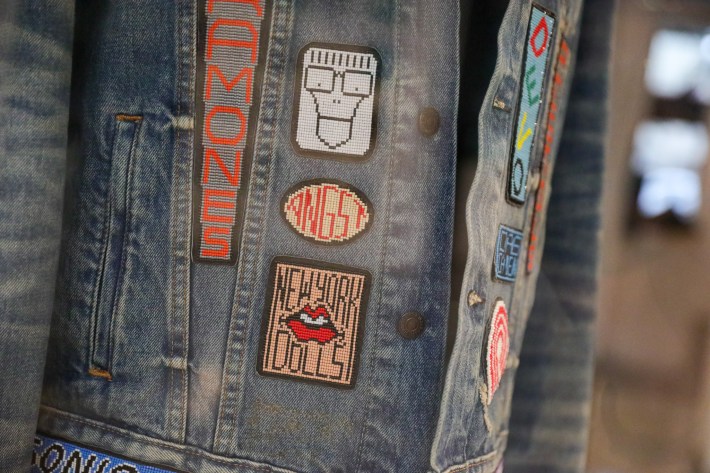

These objects are as good a representation of prison life as I’ve seen in an art show. One gets a sense, from studying them, of the deep isolation suffered by incarcerated people. Below a jean jacket beaded with the patches of many musicians, Livingston writes about his experience during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, living almost entirely locked down in his cell, learning to bead. Many of us experienced lockdown in larger or smaller degrees; Livingston invites the viewer to imagine near-total lockdown behind steel bars, in a 6x10’ cell, with one other person, for 18 months. The beaded jean jacket, he notes, contains over 90,000 beads.

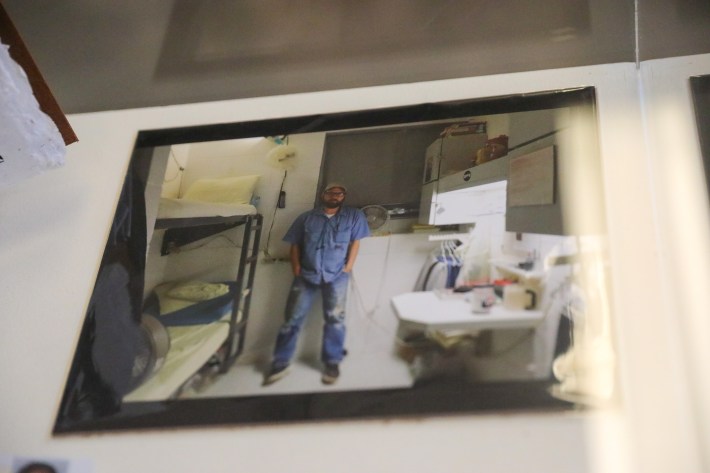

This show is worth seeing for both the concert posters and for the powerful sense of life inside prisons that Livingston offers us. On one pillar sits a rigged prison screen press with a false base, accessible by taking out a few specific screws, where Livingston would hide “screw drivers, knives, files, all the things needed for me and my friends to create our crafts.” The show is a potent reminder of one’s own freedom, if one chooses to use it; count yourself lucky if you do not have to hide away your paintbrushes and pens.

Music and art are, for many, ways to stay sane. In “A Relentless Pursuit,” Livingston—who now owns Sunset Club Records on Studio Row—uses his particular fusion of music and art to point to something even more basic: freedom of expression, and the power and skill that come from that expression. It’s not something to be taken lightly or for granted; it’s something that can be easily taken away. Use the freedom you have, Livingston seems to tell us—while you still have it.