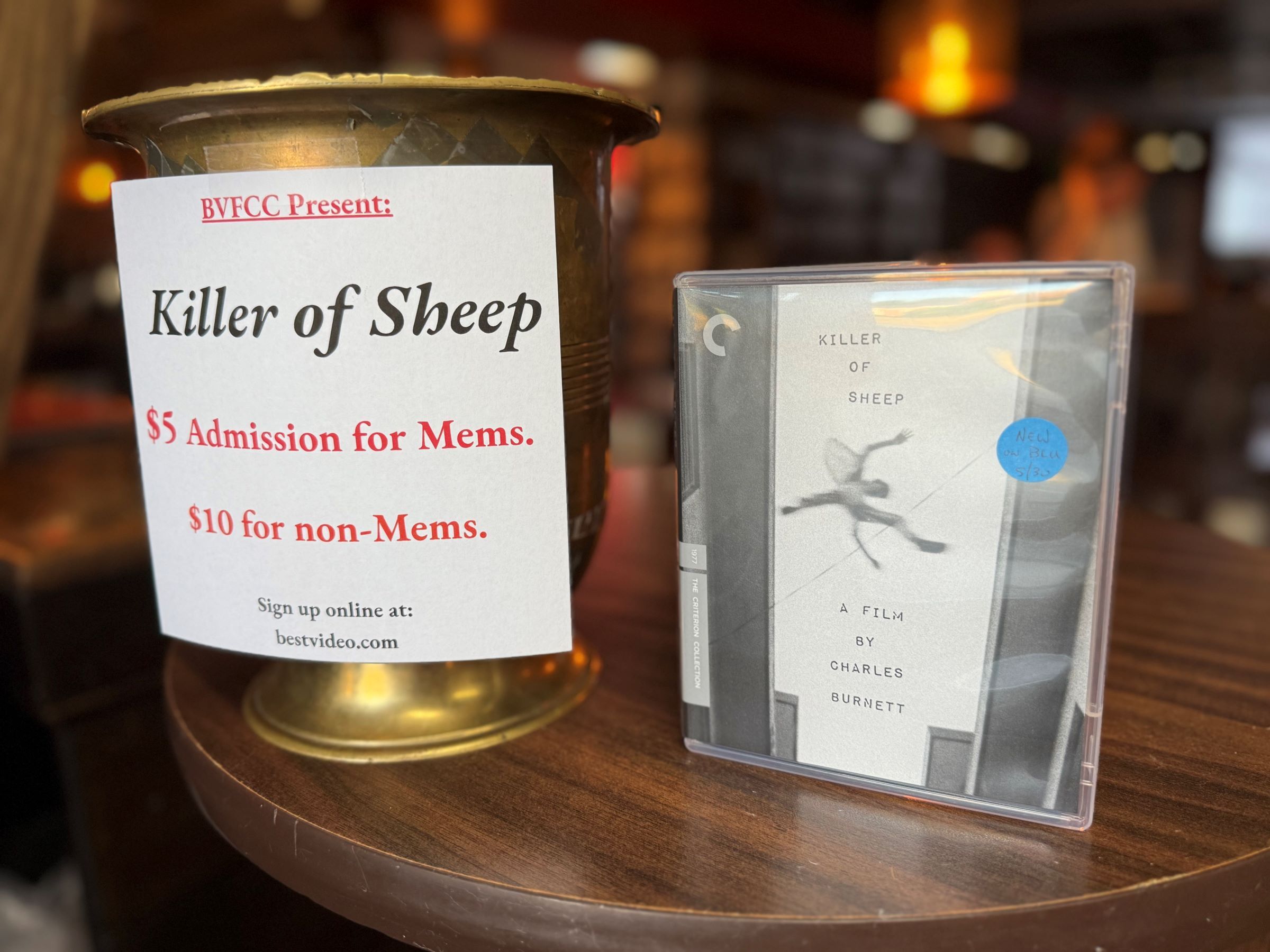

Summer at the movies is typically a time for effects-laden blockbusters and flashy remakes, but on Tuesday night, Best Video boldly offered a realistic independent drama from the 1970s that provided more food for thought than snack-accompanied spectacle.

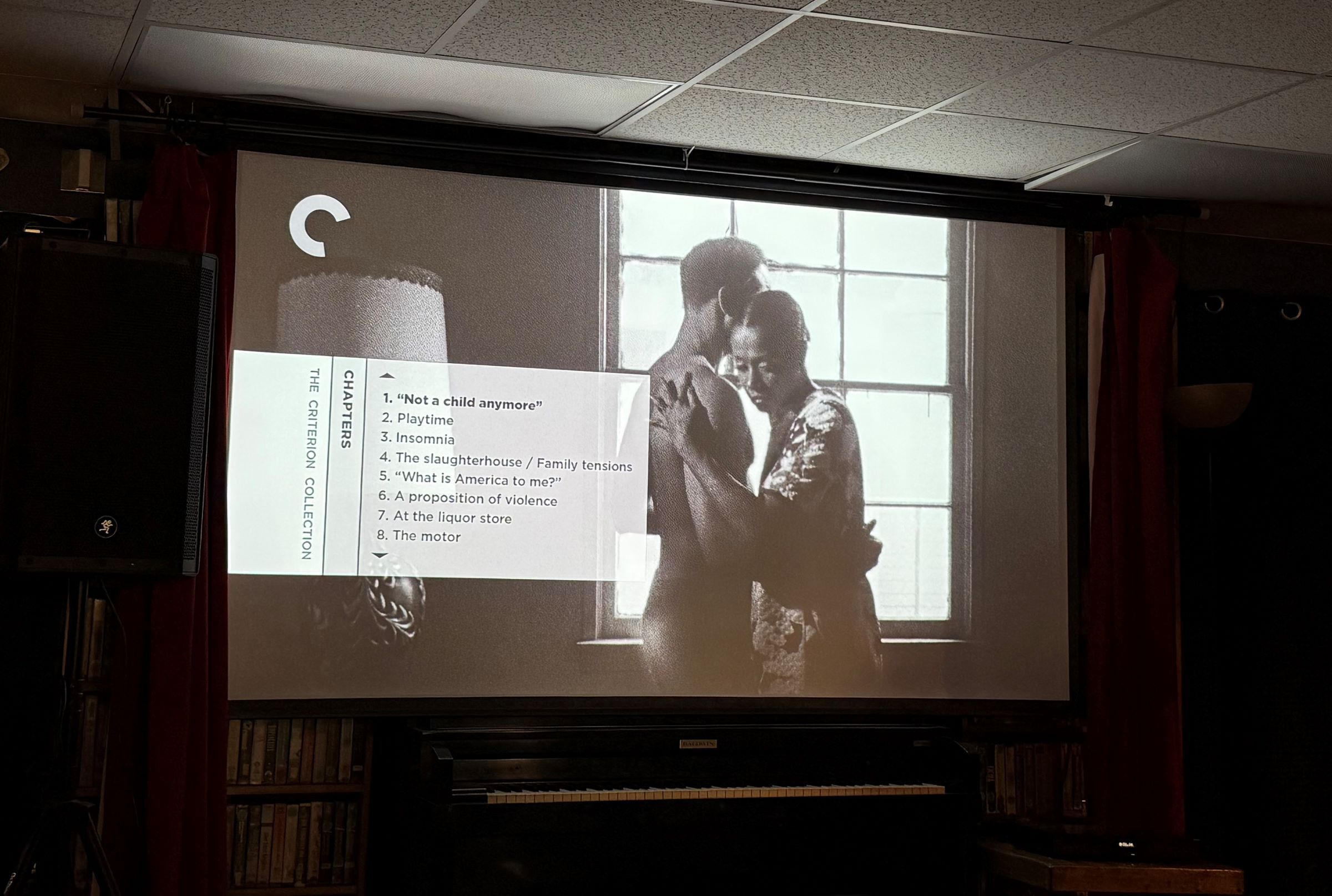

Killer of Sheep — the 1978 film written, directed, produced, edited, and filmed by Charles Burnett — engrossed a room full of film lovers with its indelible images and slice-of-life approach to its subjects: an African American family and their friends making their way through their days and nights in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles in the early '70s.

The film centers on the fatigue-ridden Stan, played by Henry G. Sanders; his wife, played with melancholy by Kaycee Moore; and his children. Through the course of the story, we see them interacting with each other as well as neighbors, friends, coworkers, and plenty of other children, who mostly are seen doing what children do: riding bikes, throwing rocks, and playing in the dirt.

The narrative is limited, but effective. Stan works in a slaughterhouse, but is looking for other ways to make money even though he can’t sleep at night and is terminally exhausted. The struggle of getting by hangs over him and all of the other adults in this film, juxtaposed with the children playing and roughhousing with each other.

Some might have a hard time with this film as it does not offer what most films typically do: a tangible plot and characters that change throughout the storyline. But what it does offer is a long, hard, yet loving look at this neighborhood and its inhabitants. One of the beauties of independent films is their ability to get you engrossed in what engrosses the filmmaker. Burnett clearly cares for these characters and asks the viewer to take the time to care for them, too.

For instance, Stan’s daughter is seen in her rubber dog mask multiple times, a mask that seems both frightening and endearing. Later on, she is heard singing the song “Reasons” by Earth, Wind, and Fire to her doll while her mother does her makeup in the next room. Those scenes bring both a joy and sadness to her character in such a short amount of time as we watch her escape her reality in two distinctly different ways.

There is also the brutal realism of the slaughterhouse where Stan works that the viewer is not shielded from. These scenes can be difficult to watch, but leave an impression not soon forgotten. Burnett even films the sheep with reverence, playing with light and shadow as he shows them making their way to their undeniable fate.

The ending cannot really be spoiled, but I won’t give away too many more details because the film needs to be seen for what it is: not a story with a definitive beginning, middle, and end, but an experience. Those kinds of films continue to exist, and I have a feeling Burnett’s film helped, and continues to help, that happen. According to Best Video’s event page, Killer of Sheep did not have a wider release on big screens until 2007 with a DVD later that year as well. It has also been preserved by the Library of Congress in the U.S. National Film registry for being “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.” This reporter and film lover would guess it was all three.

Best Video’s next screening is Tuesday, Aug. 19 in conjunction with Lyric Hall, and it will be 2005’s Brokeback Mountain, directed by Ang Lee and one of this reporter’s favorite films ever. More information about any of Best Video’s film screenings, both at their Hamden location and at Lyric Hall, can be found on their website.